Schlagwort: ‘Meningitis’

Tick Tock, TBE O’Clock: Your Exam-Ready Guide about Tick-Borne Encephalitis

Disclaimer!

This article and its major media content are produced by students to train science communication as part of a lecture about human infectious pathogens. The article does not represent official advice from the authorities. For authorized information about the disease in question, please refer to the official health authorities in your country or the World Health Organization.

By Franziska Fohn, Gina Auerswald & Jana Egner-Walter

Do you know this moment, where you realize you procrastinated a bit too long and now your virology exam is approaching? Don’t worry! In just a few minutes, here you will learn all the important molecular mechanisms and clinically relevant facts about Tick-borne encephalitis (TBE)—everything you need to answer every question with confidence!

How can TBE replicate and invade the brain?

_

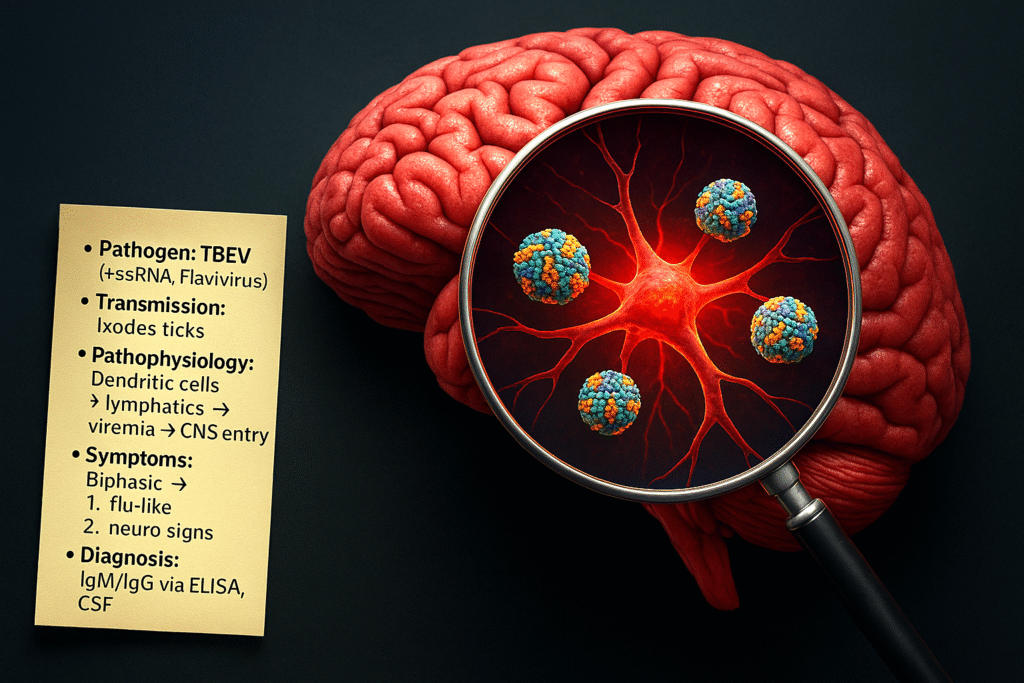

TBE is an infectious disease caused by the TBE-virus (TBEV), a member of the Flaviviridae family. It’s a +ssRNA virus that is transmitted by the saliva during the bite of infected ticks, in Europe mainly Ixodes ricinus. Different properties of tick saliva, such as its antihaemostatic, vasodilatory, and local immunomodulatory activity contribute to the facilitated transmission of TBEV. The virus’s life cycle starts with the uptake of the virion into dendritic skin cells and macrophages via the viral envelope E protein. In these cells, the virus replicates and reaches the lymphatic system. From here on, the TBEV reaches systemic blood circulation, spreading to local lymph nodes and later the spleen, liver and bone marrow. If it breaches the blood-brain barrier (BBB), it reaches the central nervous system (CNS), leading to meningitis or meningoencephalitis. Possible routes by which TBEV may breach the BBB include peripheral nerves; olfactory neurons; transcytosis through vascular endothelial cells of brain capillaries; and diffusion of the virus between capillary endothelial cells. The primary targets of TBEV infection in central nervous system are neurons.

▶ Want a visual explanation of the replication cycle, spread and how neural tissue is affected by TBEV? Check out this 3-minute video from our YouTube Playlist: “Virology with Dr. Vee”*!

How does TBE present clinically and how would you diagnose it?

TBE progresses in a biphasic manner:

- Phase 1 (~ 5 days): After an incubation of about 8 days, the infection starts with flu-like symptoms → fever, fatigue, body aches

- Phase 2: After an asymptomatic week (which may include leukopenia and thrombocytopenia), the virus may attack the CNS → high fever, headache, nausea vomiting, impaired consciousness → meningitis, meningoencephalitis, meningoencephalomyelitis.

During this second phase, typical lab findings include lymphocytic pleocytosis and a higher erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR). To confirm TBE diagnosis, two criteria must be met:

-

- Clinical signs of CNS inflammation

- Detection of TBE-specific IgM or IgG in the serum or cerebrospinal fluid (CSF)

Additionally, C-reactive protein (CRP) levels may also be elevated and serve as a marker for disease severity.

▶ Want more information about the clinical experience? Listen to the TBE episode of the podcast “Health Talks”*, in which a patient shares their story, and neurologist Dr. Bennett** provides additional medical insights.

_

How does the TBE vaccine protect from infection?

Since there is no treatment for TBE, prevention through active immunization is crucial. All licensed vaccines against TBEV are based on inactivated whole viruses, containing various TBEV strains. The E-proteins on these inactivated viruses are recognized by dendritic cells through their toll-like receptors (TLRs), leading to the phagocytosis of the particle. The viral proteins are processed and presented on the dendritic cell’s surface via the MHC class II. When migrating to the lymph nodes, they activate CD4+ T-cells, which induce the production of specific antibodies against the TBEV surface markers in plasma cells. In case of a future exposure to TBEV, the antibodies enable a fast recognition of the virus.

Self-test for optimal understanding:

So now that you’ve read all the information, can you answer these (extremely exam-relevant) questions?

- Through which routes may TBEV breach the BBB?

- How does TBEV replicate?

- Which symptoms indicate TBE and how can you confirm the diagnosis?

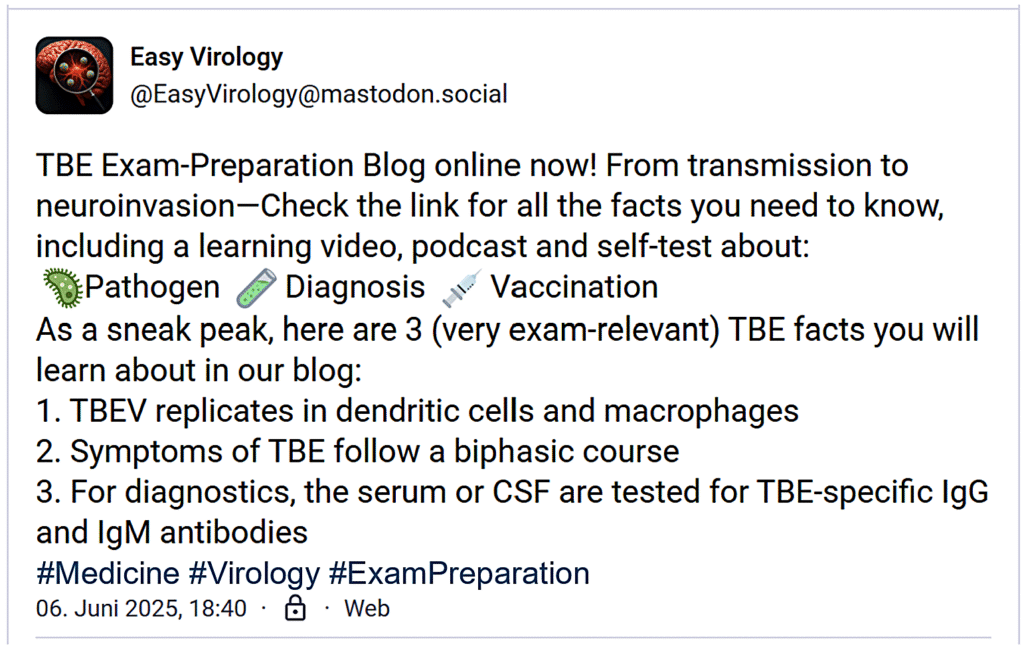

Don’t forget to follow our Mastodon Account @EasyVirology to stay tuned about upcoming virology study posts!

*fictional YouTube Playlist/Podcast

**fictional character

_

References

- Chiffi G, Grandgirard D, Leib SL, Chrdle A, Růžek D. Tick-borne encephalitis: a comprehensive review of the epidemiology, virology, and clinical picture. Rev Med Virol. 2023; 33(5):e2470. https://doi.org/10.1002/rmv.2470

- Bogovic, P, and Franc S. Tick-Borne Encephalitis: a review of epidemiology, clinical characteristics, and management.“ The Lancet Infectious Diseases, vol. 19, no. 4, 2019, pp. 469–478. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(18)30454-1

- Kaiser, R. Clinical manifestations and diagnosis of tick-borne encephalitis. Journal of Neurology, vol. 267, no. 2, 2020, pp. 276–282. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-020-09936-w

Traveling to Africa as a Gap Year Adventure: Understanding the Risk of a Meningitis

Source: pixabay

Disclaimer!

This article and its major media content are produced by students to train science communication as part of a lecture about human infectious pathogens. The article does not represent official advice from the authorities. For authorized information about the disease in question, please refer to the official health authorities in your country or the World Health Organization.

By Franziska Broeske and Yuko Tanabe

Thinking about going on an exciting gap year adventure to Africa? Exploring new cultures, wildlife, and stunning landscapes can be an incredible experience. However, it’s important to be aware of potential health risks, including meningitis, and take necessary precautions for a safe and unforgettable journey.

The Meningitis belt

Meningitis is a bacterial infection that affects the protective membranes surrounding the brain and spinal cord. In Africa, especially in the sub-Saharan region known as the „Meningitis belt“, meningitis is more common compared to other parts of the world. Moreover, it is important to stay informed about the current infections during your trip. Keep in mind that the dry season is the most dangerous, with the risk of an infection being significantly higher. When you are interested in the latest outbreak and how the government handles the recurring outbreaks, you can read the comment, “Meningitis outbreak in Nigeria: Nigeria’s Inadequate Response to Devastating Meningitis Outbreak”, published in the newspaper TERRA*. The author criticizes the Nigerian government during the latest meningitis outbreak between October 2022 and April 2023. The bacteria involved in this outbreak are primarily Streptococcus pneumoniae and Neisseria meningitidis, which cause meningitis in young adults.

Cause and symptoms of the disease

These specific bacteria, which cause meningitis, are primarily transmitted through respiratory droplets, often spread by coughing, sneezing, or close contact with an infected person. Places like hostels, public transportation, or social gatherings can increase the risk of exposure. It is important for you to recognize the symptoms (fever, headache, vomiting …) and to be informed about the risks of a meningitis infection. Therefore, we suggest the video “Human Pathogens: Meningitis” for you to learn key facts about the infection and what actually happens in your body when you are infected with Streptococcus pneumoniae.

—

Prevention of a meningitis infection

One of the most effective ways to safeguard against meningitis is through vaccination. Conjugate vaccines are available and recommended for travelers visiting high-risk areas, including sub-Saharan Africa. Consult a healthcare professional or a travel clinic well in advance of your trip to receive the necessary vaccinations and understand the recommended schedule. To find out more about bacterial meningitis and its prevention, listen to the interview with Dr. Mark van der Linden, the head of the reference laboratory for streptococci at the Institute of Medical Microbiology at RWTH Aachen University Hospital.

—

Additional advice for a safe trip

In addition to vaccinations and vigilance, maintaining a healthy lifestyle during your trip is important. A balanced diet, regular exercise, and sufficient rest can strengthen your immune system, reducing the chances of infection. Don’t forget to purchase comprehensive travel insurance that covers medical expenses, including emergency medical evacuation. Accidents and unforeseen circumstances can occur, and having adequate insurance will provide peace of mind throughout your adventure.

Traveling to Africa during your gap year can be a transformative experience. By understanding the risks associated with meningitis and taking proactive measures, you can fully embrace the beauty of the continent, immerse yourself in diverse cultures, and create lifelong memories. Remember, your health and safety are of utmost importance, so plan wisely, stay informed, and enjoy an incredible journey exploring the wonders of Africa!

* fictional newspaper

About the authors:

Franziska Broeske

Franziska Broeske

Master student in Biology “Medical life science”

RWTH Aachen University

Yuko Tanabe

Yuko Tanabe

Master student in Biology “Medical life science”

RWTH Aachen University