Design thinking history – the impact of Stanford Prof. John Arnold

There have been quite a few attempts to trace back the origins of the “design thinking movement”. In fact, most academic works I read on this matter include an epitome of how it came to be. To this regard, I particularly want to point out Stefanie Di Russo’s excellent blog posts on the history of design thinking and the underrated writings of Bruce Archer.

Rather than doing another chronology of design thinking however, I want to shed some light on the influence of Prof. John E. Arnold (1913–1963) of the Stanford Mechanical Engineering department, which I believe had a great impact on the design thinking movement. Here’s why:

In 1957, John E. Arnold joined Stanford faculty as Professor of Mechanical Engineering and Professor of Business Administration. At that time, he was already known for his unconventional teaching paradigms for engineers, especially boiling down in his Arcturus IV case study, a problem-based learning approach that put his students in a futuristic setting to work on tools and appliances for a bird-like race having “three eyes, including one with X-ray vision” [1]. (Rumour has it that this unconventional practice might be responsible for him leaving the M.I.T., where he taught creative engineering before joining Stanford…)

“His “science fiction” approach caused a stir among traditional educators and conservative engineering leaders.”

– New York Times, September 30, 1963

It is interesting to note, that most scholars root the design thinking movement in Herbert Simon’s The Sciences of the Artificial from 1969 [2] – Stefanie Di Russo being a notable exception (see above). However, I will share some quotes from Arnold’s talk Creativity in Engineering [3] held at a New York Conference on Creativity ten years before Simon published his work. I will also briefly link them to our current understanding of design thinking.

“And fourth, in the last area, [the engineer] can take on some aspects of the artist and try to improve or increase the salability of a product or machine by beautifying or bettering its appearance, or by having a keener sensitivity for the market and for the kinds of things people want or don’t want.”

– John E. Arnold

While design thinkers usually don’t regard themselves as experts in aesthetic design, they do put great emphasis on what people want or don’t want. Most methods used in design thinking really try to improve our understanding of the user and other stakeholders somehow associated to the product.

“Questioning and fantasy are two prime requisites of the creative personality.”

– John E. Arnold

Asking questions is an essential part of design thinking. We interview people, wonder WHY things are as they are…

…and, perhaps most importantly, ask ourselves How might we do this?:

“He is looking for a broad, generic statement, something that will not pre-condition his thinking along narrow lines but will give him a broad area to explore in his search for a solution.”

– John E. Arnold

While there are a lot of similarities to our current understanding of design thinking, there is at least one very notable difference: John E. Arnold was not a great advocator of team work, as can be seen in the following quote.

“Perhaps the team on some occasions interferes with the creative process. What comes out of a team or a committee is the most daring idea that the least daring man can accept.”

– John E. Arnold

While there certainly is some truth in this, I believe working in teams can generate synergies that make up for any shortcomings that might come with it. Furthermore, if we are able to hold a design thinking mindset, the “least daring” person will not interfere with any visionary idea!

John E. Arnold died on September 27, 1963 from a heart attack in Italy, where he was on a sabbatical to write a book on the philosophy of engineering [4].

“John Arnold was a visionary thinker. Not one to follow, he set trends in design education.”

– Memorial Resolution for John E. Arnold

[1] Hunt, Morton M. 1955. “The Course Where Students Lose Earthly Shackles” LIFE Magazine, May 16.

[2] Simon, Herbert A. 1969. The Sciences of the Artificial. Cambridge, London: The MIT Press.

[3] Arnold, John E. 1959. “Creativity in Engineering.” In A Report on the Third Communications Conference of the Art Directors Club of New York, edited by Paul Smith, 33–46. New York: Art Directors Club of New York.

[4] The Stanford Daily. 1963. “Prof. Arnold Dies Traveling in Italy” October 2.

Human-robot interaction and the four-sides-model by F. Schulz von Thun

Larry Leifer lately pointed me towards the issue of human-robot relationships, which he refers to as “Hu-mimesis” in the sense, that robots might have to imitate human behavior to be accepted and trusted by its human counterparts or users, as we usually refer to them.

Larry did a great talk on hu-mimesis at mediaX at Stanford University, in which he points out three forms of dialogue in which humans and robots interact: information dialogue, emotion dialogue, and knowledge dialogue.

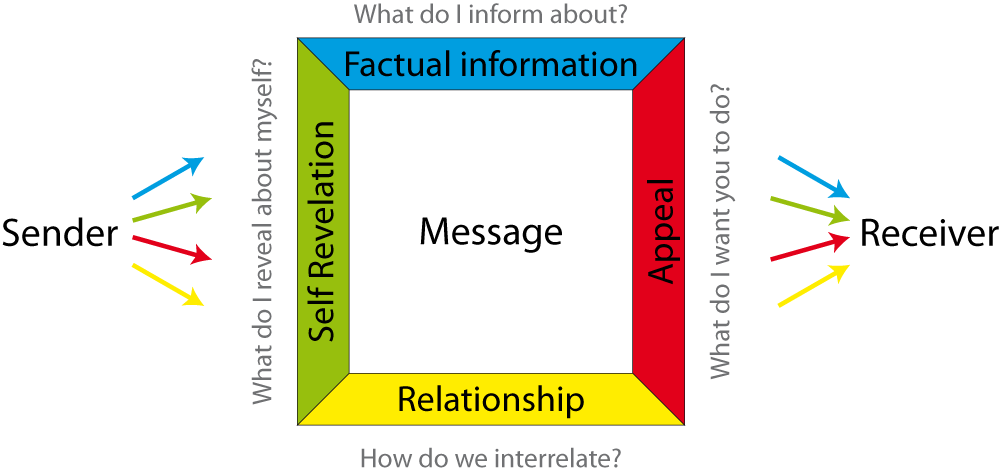

While this model does appeal to me as a communication scientist, I was immediately reminded of the four-sides-model, a model quite famous in Germany for interpersonal communication. It was developed by Friedemann Schulz von Thun and is also referred to as the four-ear-model [1].

The four-sides-model consists of the four sides factual information, self revelation, relationship and appeal, which all belong to a message. The idea is that messages can be sent and interpreted many-sided and that the recipient might not always understand what the sender intended to communicate.

The classic example Schulz von Thun uses is a man telling his wife that “the traffic light is green”, while waiting at a junction.

Factual information: The green sign is on.

Self revelation: I want to get going.

Relationship: You need my help.

Appeal: Go!

If we want humans to trust robots such as self-driving cars (independently moving you with 100 mph or so…) we need to address all four sides. This is for the simple reason that we will rather trust a human-like (or hu-mimicked) object than a technical artefact [2].

The standard example “the traffic light is green” might just have gotten a whole new meaning…

[1] Schulz von Thun, Friedemann. 2010. Miteinander Reden 1: Störungen Und Klärungen: Allgemeine Psychologie Der Kommunikation. Auflage: 48. Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag.

[2] Hinds, Pamela J., Teresa L. Roberts, and Hank Jones. 2004. “Whose Job Is It Anyway? A Study of Human-Robot Interaction in a Collaborative Task.” Hum.-Comput. Interact. 19 (1). Hillsdale, NJ, USA: L. Erlbaum Associates Inc.: 151–81.

Summary: “Understanding Radical Breaks” by J. Edelman

A while ago I came across the work of Jonathan Edelman, whose main research is on design team behavior. He specifically looks at how different media influences behavior and team performance but comes up with some other concepts, which I feel can be rewarding for you.

Jonathan used to be with the Stanford Center for Design Research and is now the Head of Programme for Global Innovation Design at the Royal College of Art, London. He is a brilliant observer and I feel like I can learn a lot from his work.

The main document about his research is probably his dissertation, which you can download for free from the Stanford Digital Repository [1]. You don’t have to do this, because I will tell you about his most important findings right now and also draw some implications from them. But if you want to dig deeper, you will have the chance to do that.

Jonathan basically video-taped design teams of three students in small group meetings working on a redesign for a “Material Analyzer”. Afterwards he would transcribe and closely analyze the videos to make sense of what people are doing when they do design. He was initially interested in how different types of media such as blueprints, rough and detailed prototypes would impact the outcome of these sessions but soon took a broader interest in behavioral design patterns. Before we start, I should mention that Jonathan’s work is qualitative, which in this case means that he dived into his material (the video-recordings) without a specific preconception of what the outcome should be. This approach can be very rich in findings but lacks a (quantitative) generalizability.

So what did he find out? The findings can be split up into three main aspects:

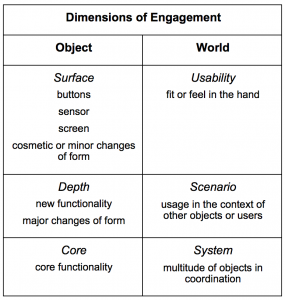

First, Jonathan came up with a framework which would allow him to differentiate between different depths of engaging with the problem (of redesigning the material analyzer) he posed to the students. Jonathan calls these “dimensions of engagement”. The framework implicates that designers engage with problems on two different levels, one being the “object” itself (which can of course be any type of entity such as a product, service or strategy) and the other one the “world” around it. You can find the “dimensions of engagement” and examples specific to the material analyzer in the table below.

For example, a design team might redesign the surface of an object by discussing the necessity or arrangement of buttons

Not surprisingly, those teams whose statements, lists, sketches, and gestures (which Jonathan counted and categorized) indicated towards deeper levels of redesign, derived further from the original design than others. Nevertheless, teams who chose to work in shallower fields, were able to optimize the product.

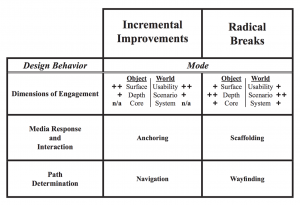

Second, Jonathan looked at how different kinds of media might influence team interactions (entitled “media response and interaction”). He eventually differentiates between two behavior classes, namely anchoring and scaffolding. (These terms derived from improvisational theater.) While anchoring happens when designers block somebody else’s suggestions using the media they work with, scaffolding happens when suggestions are built upon, using the media they work with.

I am including pictures of the media (prototypes) that the teams received below. While the cardboard puck and the experience-like model are both poorly defined, the foam model is well defined. What differentiates the former two is their abstraction levels: The experience-like model is more concrete than the cardboard. (If you are curious about the underlying media models framework, you can read about it in chapter 1.4.5 of Jonathan’s dissertation.)

Interestingly, the teams that received experience-like models rather used it for scaffolding, while teams with a foam model used it for anchoring. Teams who received a cardboard puck did not use it for either.

Third, Jonathan looked at how designers move through “perceptual landscapes”, i.e. which ideas they consider and/or follow. For that, he coins the terms wayfinding and navigation, subordinated under “path determination”. While wayfinding means finding one’s path by following “direct perceptual cues”, navigators follow a predefined path, usually the shortest one possible. This implicates that wayfinders take longer to get to the goal, but also see more of the landscape they pass.

Now for me, the most important result of Jonathan’s study is the connection and interpretation of these three aspects: dimensions of engagement, media response and interaction, and path determination. This is partly done within the “innovation behavior framework” shown below.

What it basically says is, that teams who

- engage with worlds and objects on a deeper level

- use media to scaffold, i.e. to build upon one another’s ideas

- find their way through the design process by following perceptional cues rather than following a pre-defined path

are likely to bring about radical breaks. For incremental improvements, which can be very rewarding at certain times of the design process as well (think about polishing up your product before a deadline), it is the other way around.

So what does all of this mean for your work?

I’d like to finish off with some calls to action to support radical breaks that directly derive from Jonathan’s work.

– Use edgy prototypes that do not seem to be almost finished!

– Use prototypes that focus on the user experience!

– Push yourselves to scrutinize presumptions and dig deeper.

– Think about the core functionalities and the greater context of your product!

– Build upon each other’s ideas rather than blocking them!

Can you relate to some of Jonathan’s findings? What would you want to question? Let me know your thoughts in the comments section below!

[1] Edelman, Jonathan Antonio. 2011. “Understanding Radical Breaks: Media and Behavior in Small Teams Engaged in Redesign Scenarios.” Stanford University.

[2] Buchenau, Marion, and Jane Fulton Suri. 2000. “Experience Prototyping.” In Proceedings of the 3rd Conference on Designing Interactive Systems: Processes, Practices, Methods, and Techniques, 424–33. DIS ’00. New York, NY, USA: ACM.

What is design thinking?

In my first post I would like to share with you what design thinking means to me.

When people ask me what design thinking is, I usually encounter one major problem: design thinking is by no means defined, so the term might have different meaning depending on the person you talk to. So what I will tell you about design thinking might be something completely different to what, let’s say an SAP manager will tell you. Having said this, there is an excellent study on design thinking in organizations that has been published recently, which also looks at its understanding and application. It’s called Parts without a whole (Schmiedgen et al., 2015) and was conducted by scholars from the Hasso-Plattner-Institut, Potsdam. I will try to wrap up the relevant sections for you:

Design thinking is usually seen as an iterative process for problem solving. This process particularly focuses on empathizing with users and thereby helps to develop human-centered products or services. It also helps to organize collaboration. Lots of people also regard design thinking as a mindset, advocating exploration, ambiguity, optimism and future-orientation (Schmiedgen et al., 2015; Hassi & Laakso, 2011).

I am aware that this summarization sounds like just another string of buzzwords. In fact, it scores a whooping .94 on the BlaBlaMeter – how much bullshit hides in your text?. So let’s dig deeper into how design thinking is actually used.

To understand this, it is helpful to distinguish between mindsets, methods and tools, all of which can be linked to design thinking. While mindsets are very abstract and hard to obtain, methods are easier to work with. Tools even more so.

So what methods are used to do design thinking? To me, it all boils down to four major methodological approaches:

Diverse collaboration: It is very helpful to solve problems in diverse teams. Team members can bring different competences to the table and – even more important – will scrutinize convictions of their team mates, which will lead to reasoned results. People who use design thinking will often use whiteboards and post-its as tools to support and foster collaboration, e.g. during brainstorming sessions or to keep track of their project’s process.

User-centeredness: Almost all the problems we are solving in today’s world have one or more human beings as stakeholders (we probably would not try to solve it elsewise). Typically we are developing a product or service for a user. To do this, design thinkers often interview and observe users in their everyday life or – later on – using a prototype of solutions they came up with.

Prototyping: Design thinking is an iterative process, where solutions are constantly improved to get to the final product. Therefore, it is helpful to use prototypes to understand user needs and the feasibility of solutions one comes up with.

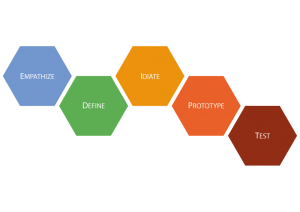

Five-step iterative process: Finally, design thinking is often taught as a five-step iterative process, for example at the d.school, Stanford University. This is used as a framework for less experienced design thinkers.

Now, a lot of people (including me) will argue that the usage of tools and methods that link to design thinking does not mean you are design thinking. In fact, I would even argue that design thinking is possible without using any of its particular methods or tools, namely just by applying a design thinking mindset to a problem. But in order to understand and practice design thinking as a mindset, methods and tools are a very helpful starting point! They will foster the design thinking mindset, meaning that they encourage exploration, ambiguity seeking, optimism and future-orientation (taken from my bullshit paragraph above…).

So to wrap it up, design thinking is not so much a methodology but rather a mindset that helps finding great solutions to problems. Nevertheless, to get started with design thinking it helps to use certain methods and tools, which foster and support the particular mindset we are looking for.

P.S.: If you are looking for a description of “design thinking methods”, you can find a good overview here: DesignKit by ideo.org.

Hassi, L., & Laakso, M. S. (2011). Conceptions of design thinking in the management discourse. Proceedings of the 9 Th European Academy of Design (EAD), Lisbon.

Schmiedgen, J., Rhinow, H., Köppen, E., & Meinel, C. (2015). Parts Without a Whole? – The Current State of Design Thinking Practice in Organizations (Study Report No. 97) (p. 144). Potsdam: Hasso-Plattner-Institut für Softwaresystemtechnik an der Universität Potsdam. Retrieved from http://thisisdesignthinking.net/why-this-site/the-study/

Graphics based on works by Lil Squid, Yazzer Perez, and Chris Gregory from The Noun Project.

![John Arnold with his unconventional props for creative engineering [1]](https://blog.rwth-aachen.de/designthinking/files/2016/01/arnold-john_life_1955-267x300.png)