Kategorie: ‘Allgemein’

Otto-Junker Prize 2025: Two ETIT Graduates Honored

This year’s Otto-Junker Prize 2025 brings double success for our faculty:

Two ETIT graduates have been honored for outstanding academic achievements.

Foto: Andreas Schmitter

Antoni Chajan was awarded for his excellent master’s thesis on topology detection in electrical distribution grids using machine learning, supervised at IAEW by Prof. Andreas Ulbig. He now works as a project engineer at FGH. In the photo: front row, second from the right.

Fenja Celine Lobenstein, Industrial Engineering – Electrical Power Engineering, completed her T.I.M.E. double degree at RWTH and CTU Prague with distinction. Her master’s thesis on the prediction of prices and market values of cross-zonal balancing capacities was supervised by Prof. Albert Moser at IAEW. Since 2025, she has been working as a portfolio manager at the energy utility Bonn/Rhein-Sieg. In the photo: front row, second from the left.

The Otto-Junker Prize is awarded annually to graduates of the Faculty of Electrical Engineering and Information Technology as well as the Materials Science group. The awards were presented by RWTH Rector Prof. Ulrich Rüdiger and the Otto Junker Foundation Board.

We warmly congratulate our award winners and celebrate this strong achievement for ETIT!

Four RWTH researchers admitted to the German Academy of Engineering Sciences

The German Academy of Science and Engineering, acatech for short, has accepted four scientists from RWTH Aachen University as new members: Fabian Kießling, Max Lemme, Constantin Häfner and Walter Leitner.

acatech is the central voice of technical sciences in Germany and is funded by the federal and state governments as a national academy. It advises politicians and society independently, factually and in the public interest on issues relating to shaping the future of technology. Its members come from the fields of engineering and natural sciences, medicine, and the humanities and social sciences. The patron of the academy is the Federal President.

With the admission of the four new members, a total of 35 scientists from RWTH Aachen University are now part of acatech. In addition to Professor Max Lemme, Professor Rainer Waser, Professor Dirk Uwe Sauer, Professor Jürgen Roßmann, Professor Rik W. de Doncker and Professor Steffen Leonhardt from the Faculty of Electrical Engineering and Information Technology are also members of the academy.

Max Lemme: Research into the electronics of the future

© Martin Braun

Professor Max Lemme holds the Chair of Electronic Components at RWTH Aachen University and is managing director of AMO GmbH. His research focuses on novel electronic and optoelectronic components based on two-dimensional materials such as graphene. The aim is to integrate these materials into future micro- and nanoelectronics, sensor technology and neuromorphic computing systems. Lemme is also spokesperson for the NeuroSys future cluster.

In addition to him, three other outstanding researchers from RWTH Aachen University were accepted into acatech: Professor Fabian Kießling, Director of the Helmholtz Institute for Biomedical Engineering and pioneer of molecular imaging, Professor Constantin Häfner, Director of Research and Transfer at the Fraunhofer Society and expert in high-power lasers, and Professor Walter Leitner, Chair of Technical Chemistry and Petrochemistry and Director at the Max Planck Institute for Chemical Energy Conversion.

Their admission recognises their scientific achievements and their contribution to the further development of technical sciences in Germany.

Rethinking Energy – A Conversation with Prof. Dirk Uwe Sauer

As part of RWTH’s interview series “Big Questions,” Prof. Dirk Uwe Sauer, head of the Institute for Electrochemical Energy Conversion and Storage Systems (ISEA) at the Faculty of Electrical Engineering and Information Technology, talks about the energy transition, technical solutions, and the responsibility of science and politics. Prof. Sauer has been researching battery system technology, energy storage, and the integration of renewable energies for many years—key topics for a climate-neutral future.

The complete conversation is reproduced below in its original sequence.

An accompanying video on the occasion of the presentation of the NRW Innovation Award also offers insights into his work and motivation:

🎥 Watch on YouTube

Foto: Heike Lachmann / RWTH Aachen University

Energy transition – what does that mean?

Professor Dirk Uwe Sauer: It means that we have to stop using fossil energy sources. These are used not only for electricity and heating but also heavily in the chemical industry. By using these carbon-containing substances that have been stored for millions of years, we increase the CO2 content in the atmosphere, which leads to global warming. We are not undertaking the energy transition for fun or because fossil energy sources will soon be exhausted—as the Club of Rome still assumed around 1970. Rather, we must leave them in the ground to keep the climate manageable. This requires a fundamental transformation of our entire society. Affected are power generation, mobility, industry, and all private households with their heating systems. Global trade flows will also change, particularly due to shifting dependencies in the procurement of energy sources. For many countries whose economies are based on the extraction and export of fossil energy sources, this poses a dramatic challenge.

Now it’s about acting quickly…

Sauer: Exactly, we are late. The consequences of climate change are already visible and are occurring more quickly and more severely than the average of climate models predicted. We are moving within worst-case scenarios. The dangers are enormous: In addition to more frequent extreme weather events, there are already major impacts on biodiversity. A weakening of the Gulf Stream is also possible, which would have irreversible, dramatic consequences for our climate. Sea levels are rising due to the melting of glaciers and ice sheets, for example in Greenland and Antarctica, but also due to the expansion of water as it warms. Meanwhile, temperature increases of up to 3 degrees compared to pre-industrial times by 2050 are already considered possible. Central Europe will initially warm more than the global average. Therefore, we must not lose time on the most important measure against climate change: ending the use of fossil carbon-containing energy sources as quickly as possible. The positive thing is that thanks to 30 to 40 years of research and development, we have solutions. Now it’s about implementing them with the necessary speed.

What do you personally contribute to the energy transition?

Sauer: I studied physics 35 years ago with the clear goal of working in the field of sustainable energy. For me, this is not just a profession but a vocation. Since 1992 I have been continuously active in the field of energy transition and energy system transformation, with a focus on energy storage, especially batteries. For about 13 years I have been involved in policy advice through the national academies of science. We try to advise politicians scientifically in an interdisciplinary way. Unfortunately, our proposals are often only partially adopted, which can be frustrating—especially when predicted problems later actually occur.

Who opposes your forecasts and why?

Sauer: If only we knew that precisely… Industry today hardly opposes anymore. In the past, there was still clear resistance—for example, in the early 2000s, when grid operators warned of the collapse of power grids at more than 2 to 3 gigawatts of wind energy—today we have 50 gigawatts with the highest grid stability. Automobile manufacturers also know where the development is heading, even if, as listed companies, they want to maintain their previous business model for as long as possible. The frustrating part comes more from politics: Despite clear targets, also at EU level, there are counter-campaigns for political reasons—for example against heat pumps or electromobility. This uncertainty harms economic development. The economy needs clear, equal targets for everyone—including importers. For example, for clean battery production, recycling, or CO2-free steel production. Particularly conservative political forces often prevent existing opportunities from being fully utilized. That sets us back economically. Although we would have the best conditions to develop the new energy world, other countries are overtaking us, above all China.

What are you working on at your institute?

Sauer: We are working on the electrification of various mobility sectors—from cars to trucks and buses to construction and mining machinery, aircraft, and ships. In parallel, the integration of renewable energies through stationary storage is important. More than two million people already have a photovoltaic system with battery storage at home. We have been operating a large battery storage system for eight years, which we trade on the electricity exchange to better integrate the fluctuating electricity generation from wind and photovoltaic systems into the system. The future of energy supply will be primarily determined by wind and photovoltaic systems. This is a fundamental system change: Previously, power plants were controlled according to demand, but wind and solar plants cannot be ramped up arbitrarily. Therefore, we need intelligent solutions such as battery storage and load management.

What would such intelligent solutions look like?

Sauer: An important example is the management of electric vehicles: Especially in summer, they should ideally be charged during the day with photovoltaic power. The battery capacities of EVs are considerable—60 to 100 kilowatt-hours—while an average household consumes only about 10 kilowatt-hours per day. Since cars travel only 37 kilometers a day on average, the surplus battery capacity could be used for grid stabilization—an economically interesting option, since the batteries are already paid for by the vehicle.

That means there would have to be discharge stations for cars?

Sauer: Exactly—we call these bidirectional charging points with the ability to feed electricity back into the grid. In some countries this technology is already more widespread. In Germany, implementation often still fails due to regulatory hurdles. In particular, with smart metering systems we have been lagging behind EU requirements and many other European countries for more than ten years. Despite these various obstacles, technical implementation is definitely possible.

Where does Germany stand in general by comparison?

Sauer: Germans’ self-assessment that we are pioneers in climate protection and that we are thereby endangering our industry is unfortunately wrong in many places. For example: In several European countries last year, 100 percent of new city buses were battery-electric; in Germany, the share of battery and fuel-cell drives together was under one third. We have achieved a lot in wind and photovoltaic power generation, but the current government seems to want to slow things down again. China has the highest expansion rates. There, the annual additional electricity demand grows by about three quarters of total German electricity consumption—every year. China manages to cover this additional demand entirely with CO2-free technologies, 80 to 90 percent of it from wind and photovoltaics, plus small shares from hydropower and nuclear.

Do the Chinese have a free hand and push everything through?

Sauer: Yes, exactly—primarily for economic reasons. They know that by expanding these technologies they can improve their production and quality and thus increasingly dominate the world market. Electricity from wind and sun is simply the cheapest way for China to meet its huge electricity demand. More or less as a side effect, they also achieve their self-imposed targets for limiting CO2 emissions several years earlier than planned. That’s good for the climate, but the main drivers for China are low-cost electricity and leadership in technology and production. Photovoltaic modules today almost all come from there. Wind turbines are still more diverse, but if we cannot maintain a corresponding sales market in Germany and Europe, it will be difficult to keep domestic companies.

In what way?

Sauer: Forces of inertia are partly understandable: For established car manufacturers with 200,000 employees, the transformation is more difficult than for Tesla as a new entrant. If 5,000 engineers are working on combustion engines, it is purely humanly difficult for a CEO to say that this is not the future. The transformation takes time, but clear targets are important. Due to political “hemming and hawing,” China has overtaken us in electromobility. Batteries come almost 100 percent from Asia. There are some European factories, but they then belong to the Asians. Only Volkswagen and Stellantis (including Peugeot, Opel, Fiat), together with Mercedes and Saft, are still trying to achieve their own technological sovereignty in Europe by building battery cell production plants. Because of waiting too long, we have fallen far behind.

What is the situation here in North Rhine-Westphalia?

Sauer: North Rhine-Westphalia shows how transformation can succeed—the state has steadily changed over 50 years and is therefore more optimistic than southern federal states with a strong automotive industry. People are more open to technology; new transmission grids are easier to build. Even lignite open-pit mining with village relocations met with relatively little protest because it is clear that prosperity must also be generated. The current state government wants to build 1,000 new wind turbines, which was initially ridiculed. But through correct and clever regulatory and legislative measures, the expansion is going well, with around 100 new turbines in just the first half of 2025.

Are there other leading examples internationally?

Sauer: Norway will reach almost 100 percent fully electric vehicles in new car sales this year. Many believe that electric cars are problematic in cold or mountainous regions, but in Norway—where it is colder and more mountainous than here—it works well. Countries that have converted public transport to 100 percent also show that it is possible. In Scandinavia, heat pumps have long been used despite lower temperatures. Spain is strong in expanding renewable energies, especially wind and photovoltaics. It’s difficult to say that any one country implements everything perfectly. However, the examples show that many prejudices—often fueled by political or media interest groups—are not true. Positive examples reach the public only with difficulty, while negative arguments spread much faster. That is a major problem for the introduction of new technologies.

What could generally have been done better?

Sauer: In all projects where streets in cities are opened up for cables, water pipes, and sewers, we should long ago have laid stronger power cables at the same time. Ninety percent of urban grid costs are construction work; only ten percent are the technical components. Then we would not have today’s problems integrating photovoltaic systems, EV charging stations, or heat pumps. But for 20 years we preferred to debate whether electromobility was the right path and photovoltaics too expensive, or whether heating systems should be supplied better with hydrogen than with heat pumps. In doing so, we expanded the power grids far too little. We now have to make up for all this in a short time; it’s expensive because we have to open up the streets again specifically for it. The high costs of the energy transition are not an inherent property of it, but the result of failing earlier to automatically replace what was coming and to upgrade for the future. It is certainly not due to a lack of knowledge.

Is it risky today to invest in a new oil or gas heating system?

Sauer: Anyone installing such a system today will probably have to replace it before the end of its service life, because these energies will become far too expensive in operation due to CO2 trading. Anyone who allows themselves to be tempted by deliberately spread disinformation to install old technologies again will pay dearly for it. Many will then call for government assistance because they will have to remove their systems prematurely. This economic loss was foreseeable. Again: If we had started earlier, the transition would have been easier. No one is demanding that functioning heating systems or cars be scrapped. But new ones must be emissions-free. The high costs could have been avoided if action had been taken in good time.

Wind and sun do not supply energy constantly—how can security of supply be ensured even with a high share of renewables?

Sauer: At present we have about 60 percent renewable energy, and security of supply is ensured. For further assurance, several components are important. The expansion of the electricity grids is essential to transport energy over greater distances within Germany—for example, from the windy north to the sunny south—but also across borders to all our nearby and distant neighbors and partners in Europe.

For energy storage we distinguish two main classes: first, battery storage for day-to-day balancing, which stores solar power during the day and releases it at night; and second, long-term storage for periods of up to three weeks with little wind and sun. These work via hydrogen gas or hydrogen derivatives, which can be stored and later converted back into electricity in power plants or fuel cells. The future energy system thus consists of power generators, power grids for spatial energy exchange—including with neighboring countries—and storage for temporal balancing. Since storage does not itself generate electricity, its quantity should be kept as small as possible. Electric vehicles can make an important contribution. Industry can also adjust its electricity consumption according to the exchange price. Heating systems with enlarged water tanks enable a temporal decoupling of heat generation and consumption and thus also play a major role as a flexibility technology.

In what way?

Sauer: In the early morning hours, we have high demand in heating systems because people need hot water for the bathroom and because the heating systems ramp up again after the nighttime setback. At that time there is no solar power generation yet. One solution is to run the heat pump the day before at midday when there is plenty of sun and store the heat in the thermal storage tank. This can then be used 12 or 18 hours later to supply the house. A water-based thermal storage tank is very inexpensive—cheaper than battery storage. For electric vehicles, it’s about intelligent charging solutions. Although a single car can be charged quickly in an hour or even a quarter of an hour on the highway, the statistical average is relevant for Germany’s 48 million cars. Since vehicles are parked 23 hours a day on average, there is a lot of temporal flexibility in charging. This can be used to charge when it is energetically sensible.

So a whole energy system is needed?

Sauer: Correct. In the past, the transport, electricity, heat, and industrial sectors were separate. Today we speak of sector-coupled systems. Power generation is coupled with heat and gases. Fuels are also produced via electricity. For planes and ships, we need hydrogen. Worldwide, 500 million tons of oil are used for plastic production. These must be replaced in the long term by electricity-based, chemically identical oil substitutes. Even if only 200 million tons remain, the electricity demand for this is a multiple of Germany’s consumption. New supply chains are emerging. We will continue to exchange electricity with neighbors and import hydrogen or products made from it, such as ammonia.

Could you elaborate on that?

Sauer: One example is the planned import of ammonia from Saudi Arabia, where large photovoltaic plants with electrolyzers (devices that split water into hydrogen and oxygen by electrolysis) from thyssenkrupp nucera are being installed. Ammonia—produced from atmospheric nitrogen and hydrogen—is a feedstock for fertilizer and consumes almost half of today’s hydrogen. Up to now, ammonia has been produced from natural gas, which is why food prices also rose after the Russian invasion.

One advantage of future energy supply is independence from the few countries with fossil reserves. Wind and sun are available in many countries. Over the long term, Germany spends around 80 billion euros on energy imports, often from countries that are not very close to us politically. Renewable energies will lead globally to greater equality of prosperity because they are available in many places. This new energy world holds opportunities, but many people are still too afraid of change.

How can we alleviate the public’s fears?

Sauer: Unfortunately, science usually reaches only a smaller part of the population and is then perceived there as a weighty voice. I also see it as my task to reach out to the public. I am a civil servant of this country; I am paid by people’s taxes, so I am also responsible for providing them with information. Although science communication is not considered a core academic task, I consider it important. We work closely with the press and give lectures. However, the skeptical part of the population, such as Aachen residents with reservations about heat pumps, remains difficult to reach. Together with politicians and journalists, we look for suitable formats to reach these people. Populist methods are out of the question for me—I can only try to disseminate good information through the press.

You briefly mentioned nuclear power earlier—will it play a role in the future or not?

Sauer: Nuclear power is a very complicated topic, and we have to distinguish two things. On the one hand, there is nuclear fission in classic nuclear power plants; on the other, there is nuclear fusion, which we have been discussing intensively for about 50 years. Fusion is about fusing light atoms—as happens in the sun, where hydrogen is fused into helium. This process is to be replicated on Earth. Very large amounts of energy can be released, and there is currently a certain global hype about it, which is also being picked up politically. There are indeed some lines of development that give new hope, but our academies project—after discussions with colleagues from companies, startups, and academia—has shown: Before 2050 there will be no commercial fusion power plants, at least not to an extent that could make a significant contribution to global power generation. That is problematic because by then we must already be CO2-free. And since it is still completely unclear whether such power plants will exist that are also economically competitive, we must plan the transformation of the energy system without fusion. I still believe that society can and must afford to continue research in that direction.

What about nuclear fission?

Sauer: In nuclear fission, all the nuclear power plants built in Europe in recent years have become two to five times more expensive than originally planned and were completed with delays of five to fifteen years. There are no economically viable new nuclear builds in Europe. In France, new plants are being planned, but it is completely unclear who will pay for them. The French Court of Audit recommends a moratorium on expansion plans until reliable financing plans are available that are also sustainable in the market. The safety risks are often underestimated—of 700 nuclear reactor blocks, five have gone into core meltdown. Nuclear power plants are not insured; the risk is borne by society as a whole. Another problem is the proliferation of nuclear technology: As long as there is civilian nuclear power, the spread of nuclear weapons can hardly be prevented. The path from civilian use of nuclear power to an atomic bomb is very short.

How can individuals contribute to the energy transition?

Sauer: The switch to electromobility and heat pumps should be designed in an ecologically and temporally sensible way. Openness to new technologies is important without overwhelming people. For areas such as green fuels, CO2-neutral steel, or sustainable plastics, political requirements are needed because end customers have little influence here. Rejecting wind power without alternatives while clinging to one’s previous lifestyle is not consistent. The press should ask more about solutions rather than just criticizing problems. Those who want less wind power or fewer power lines must accept higher electricity prices. Protest is legitimate, since the new system also requires raw materials and land, but those who reject technologies must propose realistic alternatives that do not merely shift the problems. Our standard of living should be maintained and be attainable for billions of people worldwide. Science should present alternatives and quantify their consequences, while politics and society should choose from them.

Why are you hopeful that a far-reaching abandonment of fossil fuels is possible?

Sauer: The 1.5-degree target has already been exceeded; even the 2-degree target can no longer be met. But the more we convert now, the more likely we are to achieve a better, fairer world. We reduce our dependencies through energy imports and can build an energy system that is more resilient to disruptions. After the current cost peak of the transformation, energy supply will become cheaper again. The new technologies prevail primarily for economic reasons—even under Trump, no new coal-fired power plants were built because they were uneconomical. China, African countries, and India are increasingly relying on renewable energies because prices have fallen sharply over the past 20 years. Cities with electric vehicles will become quieter and the air will become cleaner; oil and gas extraction—with its severe environmental impacts in producing countries—will decrease or disappear. Countries with currently low living standards will have a realistic chance of sustainable development, which will also reduce migration pressure. A world without fossil energy sources will be a better one.

But it is also clear that the transformation will bring major changes locally and for individuals. Industrial sites may shift, some products will no longer be needed, and some professions will no longer exist in the future. What is positive in total does not have to be positive from an individual’s perspective. Managing this process well and offering all people new perspectives—that is the real challenge.

Your forecast: What will the German energy system look like in 2045?

Sauer: Power supply will be completely CO2-free by 2045, with the aim of reaching this as early as 2035. The electricity sector is relatively easy to convert. There will be no new registrations of internal combustion engines for fossil fuels, even if some will still be on the road. Vehicle manufacturers will offer combustion engines only for niche products. The majority of trucks will be battery-electric.

For heating systems there will be a mix, with district heating and especially local heat pumps. The district heating systems will hopefully be partially supplied by deep geothermal energy. The main foundation for everything will be wind and photovoltaic systems, supplemented by smaller shares of geothermal, wave, and tidal energy. You will not be able to fly across the Atlantic on batteries in my lifetime—that is physically excluded. We will need a fuel for that—hydrogen or an e-fuel—which we will then have to produce. Therefore, a large part of the electricity will be used to produce hydrogen-based energy carriers and for the basic materials industry. In large open-space photovoltaic plants, habitats for fauna and flora will be provided between the module rows, where more biodiversity can develop again—with more wild plants, flowers, more insects, and ground-dwelling birds and small mammals.

What role will hydrogen still play in the future?

Sauer: Hydrogen will play a central role in industry—for steel production and as a feedstock for chemicals, pharmaceuticals, and plastics. In the transport sector, long-haul aviation and shipping will use hydrogen-based fuels, and perhaps, for example, agricultural machinery as well. Hydrogen is the storage medium for stockpiling during “Dunkelflauten” (periods with little wind and sun) in the power supply system. Access to hydrogen and hydrogen derivatives must be made as easy for industry as access to natural gas is today.

You specialize in batteries…

Sauer: Enormous progress has been made in this area. Twenty years ago, no one would have thought that so much money would flow into battery research. In 1994 there were only four or five people in Germany working on battery systems. I was lucky to be steered in the right direction by visionary minds. The development is gigantic, even if it could have gone faster.

Sustainability and circular economy are becoming increasingly important. The EU is introducing a digital battery passport that contains information on origin and recycling. Quotas for recycling are being stipulated because lithium is not yet recycled today; it is cheaper to mine it anew. We are researching materials that are less scarce. In the past, lithium-ion batteries required a lot of cobalt and nickel; today, stationary batteries can do without these materials. We are also working on sodium batteries—sodium from table salt is almost unlimited. As a university, we are working on more environmentally friendly materials with higher efficiency and longer service life. The greatest environmental effect is achieved when a battery lasts 20 instead of 10 years—that means half the energy input and raw materials.

What makes RWTH so special for energy research?

Sauer: RWTH is an exceptional location, together with Forschungszentrum Jülich, with which we are closely linked. Nowhere else in Germany are there as many energy researchers as here; for all questions and topics there are highly specialized chairs and institutes with several thousand people working on these issues. That’s exactly why it’s good to be here. With our CARL research center, for three years we have had—at least in Europe—the most modern university research center for battery system technology, and that opens up completely new scientific opportunities for us, always with a focus on bringing things into applications as quickly as possible.

The interview was conducted by Nicola König.

The Science of Sound and Well-Being – Inside RWTH’s MOSAIC Project

Traffic noise, birdsong, or the hum of a computer – sounds are part of everyday life. But when do they start to affect our well-being?

That’s the question behind MOSAIC (Acoustic Well-Being in a Multi-Domain and Contextual Spatial Approach), a new graduate research group coordinated by RWTH Aachen University.

Foto: Andreas Schmitter

A key partner is the Institute of Hearing Technology and Acoustics (IHTA), led by Prof. Janina Fels, where engineers explore how sound and human perception interact.

Together with Prof. Marcel Schweiker from the Chair of Healthy Living Spaces, she investigates how acoustic comfort can be measured and improved.

As Prof. Schweiker notes: “Construction noise is usually perceived as more disturbing than birdsong – but at a certain level, even birdsong becomes tiring.”

Beyond volume, the team looks at how light, temperature, and room geometry influence how we experience sound – using methods and instruments deeply rooted in electrical engineering.

At the Kick-off Meeting on October 15, researchers and representatives of the HEAD Genuit Foundation gathered to launch the four-year program.

Foundation founder Prof. Klaus Genuit, a graduate of RWTH’s electrical engineering program and an honorary professor at the university, emphasized the importance of supporting young researchers in acoustic science.

“In a football stadium, I expect a certain level of noise – I’d be surprised if it were quiet,” Schweiker added.

MOSAIC aims to capture exactly this context dependency through modern sensing and signal-analysis techniques – many of which stem from ETIT’s research tradition.

Harnessing AI for a Smarter Energy Transition

Since August, Dr. Pyae Pyae Phyo has been conducting research at the Institute for Automation of Complex Power Systems at RWTH Aachen University. As a Humboldt Research Fellow, she tackles one of the key challenges of the energy transition: the fluctuating output of renewable energy sources.

“Most power grids were designed for fossil-based generation, which provides constant and predictable energy. Renewables are different – their output depends on the weather,” she explains.

Dr. Phyo applies AI-based prediction models to make these variations more manageable and to strengthen grid stability and efficiency. Her goal is to develop and refine algorithms that can accurately forecast how much energy wind or solar plants will deliver over a given period.

Foto: Judith Peschges

Her path to RWTH was made possible by Professor Antonello Monti, who supported her through the Henriette Herz Scouting Program of the Humboldt Foundation.

“The excellent reputation of Professor Monti and RWTH in my research community was decisive for my choice,” she says.

Holding degrees from TU Mandalay and Thammasat University, Dr. Phyo has also worked in South Korea, Canada, Switzerland, and most recently at Eindhoven University of Technology as a postdoctoral researcher.

Her work builds a crucial bridge between artificial intelligence and sustainable energy systems—contributing to a more secure and efficient power grid for the future.

Observing 2D Memristors with Operando TEM: Another Step Toward Neuromorphic Computing

Understanding of conductive filament dynamics in memristive devices based on two-dimensional (2D) materials has been substantially advanced by a research team from AMO GmbH, RWTH Aachen University (Chair of Electronic Components), and Forschungszentrum Jülich.

The researchers used a transmission electron microscope (TEM), which instead of light uses a beam of electrons to make images, thus achieving imaging down to the scale of atoms through the short wavelengths of electrons. The operando state for TEM was used to observe the 2D components as they are operating, and not in before or after states. Which allows the nanoscale phenomena to be observed in real time.

Memristors are a key part of neuromorphic computing, which allows computation and memory in the same physical location so that the use of energy is radically minimized.

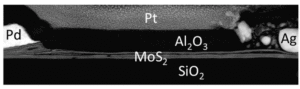

For this research, 2D sheets of molybdenum disulfide (MoS₂) were used. It is a compelling candidate for memristive devices owing to its atomically thin, layered two-dimensional structure, which features interlayer van der Waals gaps, which are nanoscale spacings maintained by weak van der Waals interactions that provide efficient transport pathways for ions and metal atoms. These pathways facilitate the controlled formation and dissolution of conductive filaments, thereby enabling the resistive switching behavior required for device operation.

Image 1 – Sheets of 2D Memristor and Pd-Ag Poles to create potential difference – nature.com

Silver ions were directly observed by the researchers as they moved through the MoS₂ medium along surface routes, within interlayer van der Waals gaps, and between bundles under applied voltage. There, they gather into metallic conductive filaments that bridge the electrodes and change the device into a low-resistance state; reversing the polarity dissolves these filaments and returns the device to a high-resistance state. In order to directly evaluate switching reliability as well as the causes of anomalous events and cycle-to-cycle variability, the operando TEM imaging is synced with current-voltage measurements. This allows them to track the nucleation, growth, motion, and rupture of individual filaments in real time and correlate these physical events to electrical signatures. They deduced the factors that influence switching performance from these observations, offering specific recommendations for the construction and functioning of devices.

These results give us specific ways to make memristive synapses more reliable for neuromorphic computing. By figuring out where silver filaments form (on MoS₂ surfaces, in interlayer van der Waals gaps, and between bundles) and measuring their sizes, the study makes it possible to better control how filaments grow and nucleate. By customizing the MoS₂ morphology and device geometry, engineers can adjust the SET/RESET voltages, limit the filament thickness, and thus improve the switching current and energy use. All of these physics-based ideas support device design and operation plans that are based on mechanisms and make memristive hardware for neuromorphic systems more stable, efficient, and scalable.

Looking ahead, as filament dynamics become programmatically controllable and device variability is tamed, neuromorphic systems could progress from lab prototypes to wafer-scale accelerators that learn on-device, operate at microwatt power levels, and approach brain-like energy efficiency. Hybrid 2D-material crossbars integrated atop CMOS may enable dense, 3D-stacked synaptic fabrics for lifelong on-chip learning, powering adaptive robotics and privacy-preserving cognition in everyday devices. With native plasticity at the device level, future machines could continuously adapt to their environments, compress and interpret sensory streams in real time, and deliver robust intelligence in battery-powered wearables and autonomous agents, bringing us measurably closer to brain-inspired computing platforms that transcend the limits of conventional digital architectures.

Source: nature.com

The illustrations were taken from the above-mentioned source. They are not in their original sizes and have been adjusted to aid in the explanation.

Software-defined vehicles and automated driving – last call in Europe for new alliances and architectures

Professor Lutz Eckstein © IKA

Lecture by Professor Lutz Eckstein, Head of the Institute for Automotive Engineering at RWTH Aachen University and President of the VDI, on Wednesday, 22 October 2025, from 5:00 p.m. to 6:30 p.m. Admission is free. The lecture/discussion will take place via Zoom and will be available as a video recording afterwards.

The automotive industry is facing major challenges. As well as electrification and automated driving, these mainly relate to the underlying hardware and software architecture that defines the functionality of modern motor vehicles. As with smartphones, it is now possible to update the infotainment system with apps and updates. However, established vehicle manufacturers are reluctant to implement a service-oriented software architecture and provide frequent updates and upgrades for safety-related functions.

Emerging competition in the field of automated driving, however, makes this necessary. From both a social and customer perspective, it would be unacceptable to respond to critical situations or even accidents only after months with a software update. While new vehicle manufacturers with an IT background are already addressing this capability with suitable architectures, established manufacturers have so far attempted to develop expensive proprietary solutions with mixed results. Consequently, there is a growing willingness within the European automotive industry to collaborate on the development and use of open-source software, beginning with the S-CORE middleware. In his presentation, Professor Eckstein will highlight the challenges involved and the further cooperation required to achieve this.

The lecture series is being held in cooperation with the RWTH Computer Science Department, Forschungszentrum Jülich, the Regional Group of the German Informatics Society (RIA), the Regional Industry Club for Computer Science Aachen (Regina) and the Aachen Group of the German University Association.

European Research Council Funds Two Groundbreaking RWTH Projects

The RWTH Aachen celebrates a major success: Two researchers have been awarded the prestigious ERC Starting Grant, each receiving €1.5 million in funding over five years.

Prof. Dr. Daniel Truhn, senior physician at University Hospital RWTH Aachen and lecturer at the Chair of Image Processing at our Faculty of Electrical Engineering and Information Technology, where he teaches the lecture “Biomedical Engineering”, is launching SAGMA (Semantic-Aware Generative Medical AI), a project that rethinks AI in radiology by connecting specialized AI modules into an expert team that supports doctors with complex diagnoses.

© Peter Winandy / RWTH Aachen University

A second grant goes to, Dr. Khiêm Vu Ngoc, at the Chair of Continuum Mechanics, is developing PolyFun (Polymer Mechanics through Function Spaces), a novel approach that combines physics and machine learning. His models are designed to be not only precise but also reliable and transparent – with wide-ranging applications in materials science, medicine, and robotics.

These grants highlight RWTH’s international recognition and the strong role of our Faculty in advancing AI and medical technology.

Talk: Digital Agriculture – More Advanced Than You Think

© KRONE Group / Jan Horstmann

Digital agriculture – more advanced than you think

Modern agricultural machinery is a high-tech marvel: equipped with powerful sensors, satellite navigation, and AI-based driver assistance systems, it significantly improves precision and efficiency in farming. Jan Horstmann, Managing Director Construction & Development of KRONE Group, provides a comprehensive overview of these technologies and practical examples in his lecture. Join the discussion and learn how digitalization is transforming agricultural technology sustainably.

The event takes place online via Zoom on September 11, 2025, from 5:00 to 6:30 PM (CET).

The video of the event will be published afterwards.

The future of battery technology: Revolution using AI

Prof. Weihan Li . © Peter Winandy

Innovative Battery Research at RWTH Aachen

Junior Professor Weihan Li is revolutionizing battery research at RWTH Aachen by developing AI-powered testing methods that enable precise predictions about the future performance and lifespan of battery cells already during the production phase.

Utilizing advanced technologies such as digital twins, data-driven models, and automated diagnostic procedures, his approach transforms traditional battery management into a proactive system—moving from mere observation to anticipatory strategies.

Shortened Development Processes and Sustainable Innovation

At the core of his research is the goal of significantly shortening development cycles, reducing production costs, and simultaneously enhancing sustainability throughout the entire battery lifecycle. Prof. Li succinctly states:

“Ultimately, we want to accelerate the development of high-quality, affordable batteries and make the entire battery life cycle more sustainable.”

The Synergy of Artificial Intelligence and Electrochemistry

Early on, Li recognized that the combination of artificial intelligence and electrochemistry is the key to the future of the battery industry. This insight drives him to push forward innovative solutions:

“That’s when I realized: this is the future,” he recalls. “Since then, I’ve been working on integrating AI and electrochemistry.”

RWTH Aachen as an Innovation Engine

For Prof. Li, RWTH Aachen is more than just a research location—it provides an inspiring environment that nurtures young talent through strong networks and a pronounced spirit of innovation. The close collaboration with industry not only underscores the demand for modern battery solutions but also secures a significant share of funding.

Data-Driven Modeling as a Key Component

The extensive data base provided by the RWTH infrastructure is a central pillar in precise AI modeling. This essential resource not only guarantees research success but also forms the foundation for highly advanced analytical methods:

“This massive dataset is essential for building our AI models.”

Proactive Battery Management

Finally, Li’s approach aims not only to monitor the aging process of battery cells but to intervene proactively—well before they reach their maximum performance limits. In his own words:

“We don’t just want to understand how batteries age – we want to intervene before aging even begins.”

The advanced, AI-enabled methods of Prof. Li at RWTH Aachen pave the way for faster, cost-effective, and sustainable battery solutions. This groundbreaking work sets a new standard in battery development and reinforces Europe’s leading role in the energy transition.